When the EU adopted it’s first-ever security strategy in December 2003 most commentators applauded. The document is probably the most understandable core document the Union has ever produced. The strategy identifies threats: failed states, weapons of mass destruction and clandestine organisations — the mode to face them: multilateral engagement — and a stick if carrots were to fail: rapid and robust intervention. Well, not quite. The document admits that the EU is not there yet when it comes to the threat or use of force and points to the need to develop a «strategic culture».

European leaders have long made clear their desire for the EU to play a greater role in international security. For this to happen they have had to face up to armed force as a policy tool. As a German statesman once put it ‘diplomacy without credible threat of force is like music without instruments.’ Since 1998 the EU states have pooled significant military capabilities, second to none in the region. The Union is currently active in two police missions in the Balkans (EUPM and Proxima) and a rule of law mission in Georgia. So far the EU has taken on three military missions: Operation Concordia in Macedonia, Operation Artemis in Congo and, in December 2004, Operation Althea in Bosnia-Herzegovina. This is no small feat considering the inglorious role played by the EU in halting the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

But there is still a gap between what the EU is handling and the sort of situation many feel that the Union should be able to handle. The current missions are all low-intensity «pre –and post crisis» operations that could have just as effectively been handled by NATO or one of the major powers. None of the missions can claim to address major issues of our day. The Iraq-war illustrated that when the pressure is on EU unity will crumble under the conflicting short-term interests of the member states. The reason why EU foreign policy has been so limited is intimately linked to the way decisions are made. The need for unanimity in Council decisions, effectively grants all 25 member states a ‘veto’ over EU policy.

The varying traditions, agendas, and capabilities of the member states offer few common denominators for a shared approach to the use of armed force. There is no shortage of fault lines pitting «Europeanists» vs. US-friendly «Atlanticists»; «introverts» vs. «extraverts»; conscription vs. professional armies; new vs. old member states, great powers vs. small states, NATO-members vs. neutrals etc. Unsurprisingly this translates into a persistent lack of agreement on where, how, when and for what reasons the EU should engage.

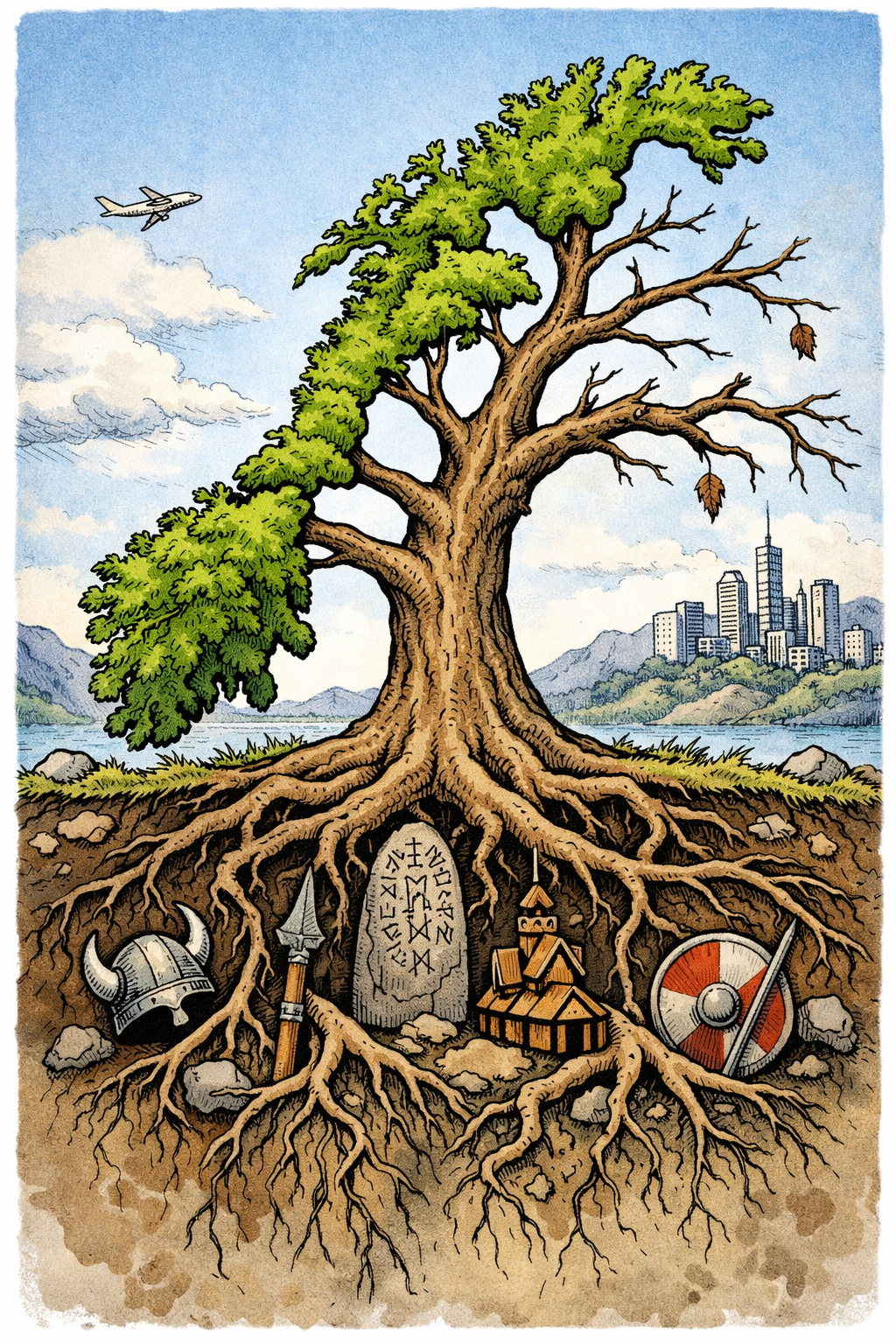

This is the problem the EU strategy refers to when it stresses the need for a ‘strategic culture that fosters early, rapid and when necessary, robust intervention’. Such a culture would define a set of patterns of and for behaviour on war and peace issues. The strategy casts strategic culture as the magical potion in one of Europe’s favourite cartoons, «Asterix» that enables the small hero to perform feats of strength for a good cause. Strategic culture is to transform the EU into a small but very effective force in world politics.

And there are signs that change is underway. The European heavyweights – France, Germany and Britain – have moved to overcoming the current log jam by simply leapfrogging the smaller countries, preparing the ground for a directorate of EU states that will develop the EU security policy further unencumbered by dissenting voices. Such an «EU Security Council» will clearly be a more effective policy maker than a «General Assembly» of 25. While it is questionable whether the aspirations of the three largest states translate into those of the EU as a whole, clearly side-lining the sort of input that made the Lisbon-process a failure could be a step in the right direction.

For the EU to be able to effectively respond, each country cannot expect to be able to go-it-alone as soon as a crisis occurs. With European scholars and politicians beginning to seriously discuss strategic culture, they have gotten the sequence right. First the EU states need to define their common interests, set out pre-defined responses for what to do when these interests are threatened and loyally support action along these guidelines. This is the yardstick by which the EU security and defence policies will be measured. Nurturing a strategic culture is the right way to making the EU a bit more like the plucky hero Asterix.

Publised by Worldsecuritynetwork 24.03-2005