The world is changing, as will international relations.

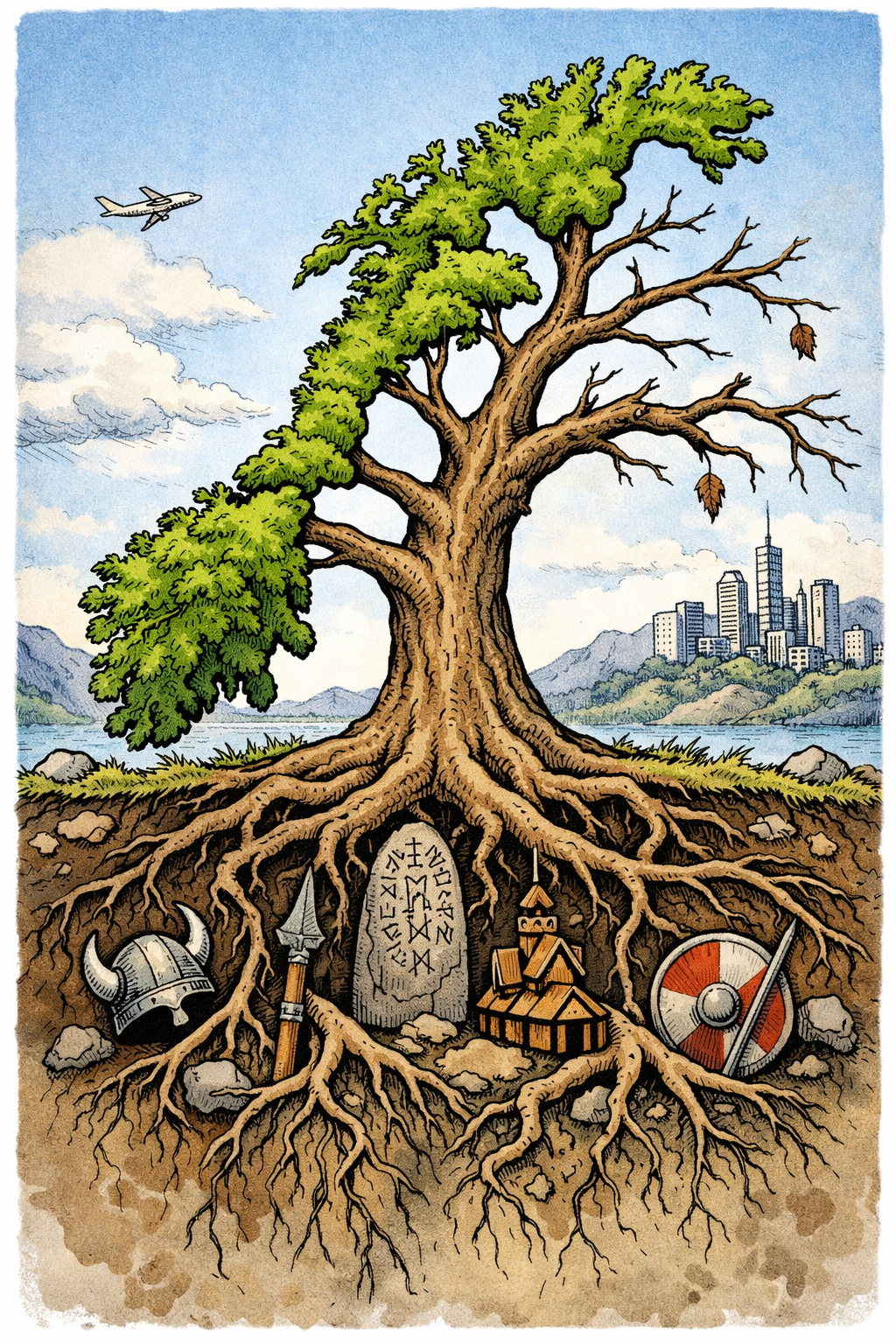

The West was never so powerful nor so influential as it was in the years immediately after the Cold War. Over time, the western community had been woven together by institutions; given a central nervous system where technologies, trade and security were shared among states in a flow of goods, services, capital, ideas and people. Not since the Hanseatic League of the late Middle Ages had small and large entities together created something so much larger than the sum of its constituent parts.

This could happen because there was an alternative model of co-operation, in the east, where the Soviet Union treated its allies as vassals. This helped awaken Western democracies to the necessity of surrendering sovereignty in order to access in the added value. The experience of the long cold war is fundamental to understanding why the West is in in flux now that the international system, the established alliances and the balance of power among the great powers is changing

In the West, we tend to interpret the new events through our historical perspective, call it “WAW”, We Always Win. And yet, this expanding order has become a defensive project where the fear of losing old gains is stronger than the urge to win new ones. The West has grown fretful. Time and time again we see that the solutions that our leaders swore to be the only defensible, fail to find their way from the teleprompter and into reality. One example can stand for many: Syria.

The West and Europe, two core concepts in American’s foreign policy understanding have lost their old meaning. Western civilization has been deconstructed and devalued. By renouncing our shared culture and history, The West has lost much of its old meaning. Europe, who had grown to see itself as akin to Athens to America’s Rome, has become synonymous with a union in permanent crisis, constantly breathing new delirious visions, like a bedridden patient on a morphine drip.

On the edge of vision, it is the ancient imperial powers are restless. Turkey, Iran, India, China, Russia – they all have the attention directed to the lands they once controlled. They all share a reluctance to let their interests be shaped by, or subordinated to, Western norms and values. Chancellor Merkel’s journey to Ankara with cash payment for its ally to halt the migration across the Mediterranean is one poignant example. It points to a world dominated by the power of states that the West do not control.

We sometimes forget that these testing times for the West is a golden age for others. This is most obvious on the Asian continent in the process of forming its own bloodstream. New roads, train lines and routes snake through the post-communist wilderness – and in the wake new institutions, new alliances follow. The combination of capitalism and authoritarianism offers an enormous potential for mobilization. In the east new megacities mushroom, faster than we learn their names.

This strength is also a weakness. China and Russia have not yet understood that democracy’s foremost advantage is not electoral politics but independent institutions. Both are internally riven by momentous societal changes and an inability of the state apparatus to keep up. This combination of growth and weakening will make the new powers unstable and unpredictable. Our current preoccupation with ‘rising powers’ overlooks the historical lesson that former great powers are a supreme source of international instability in their tendency to write geopolitical cheques they no longer have the power resources to cash.

Asia’s obsession with security cannot be understood without considering the monumental uncertainties arising from a headlong plunge into globalization and capitalism. For hundreds of millions, all the core elements of life have been uprooted and transplanted into strange, unfamiliar soil. Globalization has led to parts of the recipe for Western modernity finding new manifestations More Protestants, for example, now go to church in China than in Europe.

It is no wonder that people demand security, order and national identity. Their leaders do not want to be like the West, they want the West to make room for them. In Africa and the Middle East, the same trends have been reflected in Islamist’s internet-driven anti-modernism and emigration. Liberal immigration policy has created a new fault line in Western politics – everything seems to be about immigration, except for immigration – which is about modernity, that suddenly seems threatening.

Confronted by this change in circumstance the custodians of the international order dream of resurrecting an imagined past, of multilateral international politics orchestrated in august institutions, notably the UN. They talk of change yet offer continuity. In Europe the EU member states responded to the poor results of the liberal centre in the European Elections by installing a new leadership quartet comprised in its entirety of proponents the federalist ideas that an increasing number of voters had rejected at the ballot This is bold, but hardly wise.

Huge sums of money are used to prop up institutions and organisations lacking in willingness and ability to reform, that are -in essence – legacies of the past century. The new UN General Secretary Antonio Gutierrez has failed to draw the obvious conclusion of the members being increasingly unwilling to fund the byzantine sprawl. He has not said ‘We should do less and do it better’. Instead he spends his time fundraising and trying not to offend the permanent members of the Security Council for fear they cut his budgets even further.

So, what are the prospects for multilateralism in this emerging multipolar order? Not good. We have already seen the U.S. falling back into its Cold War habit of dealing with rival powers bilaterally, without its western partners in the room. China and Russia celebrate multilateralism in speeches, but not in policy. A host of middle-sized powers from Turkey too Iran and Brazil seem more eager to gain some of the unilateral privileges of the great powers for themselves than they are to bind the system determining powers into an international order where their power resources are restrained.

If we were students at a model UN, we would surely advocate a root and branch reform of the UN, including the Security Council combined with a ‘Marshall Plan’ for whatever happens to be the cause célèbre of the day. This will not happen. The past decade have drained the fountain of mutual trust that has enabled multilateral diplomacy in the past. We thus find ourselves in a state of unstable multipolarity.

China, Russia and the West

“It is too early to say”. Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai’s assessment of the French Revolution nearly two centuries earlier – is often cited as evidence that Chinese leaders think more long-term than others. This is a myth. President Nixon and Enlai probably talked past each other. New material indicate that Enlai was referring to the 1968 demonstrations in Paris.

Ever since Nixon’s journey to China in 1973, it has been a goal for the U.S. to prevent Russia and China from joining forces. When the two most powerful countries outside the United States alliance system seem increasingly willing to coordinate militarily, this is a harbinger, a warning of what may follow. M. A. Kaplan estimates for a multipolar order to be stable it needs to have five or more power clusters. The current system has fewer and is, thus, in flux.

The unipolar system with the United States at the top was essentially transient. The idea that “power will balance power” is the closest one comes to a law of international politics. It was to be expected that other great powers would seek to balance American dominance. Interests often trump values in international politics. And with interests come spheres of influence.

Balance of power is no new innovation, but rather a proven recipe for stability. This was the core of the Westphalian system that regulated the regional order in Europe and beyond from 1648. The goal was that no single state should grow stronger than the others combined, as philosopher David Hume suggests in his essay “On the Balance of Power” (1752).

The idea is that if great powers are tempted to coerce weaker states, this impulse will be checked if they are likely to be confronted by a powerful counter-coalition. The power balance mechanism is crude, yet effective. It prevented first Napoleon and later Hitler from establishing hegemony in Europe. Mutual fears make alliances. When it comes to survival, states with widely different governments will set aside their differences. As the communist Soviet Union and royalist Britain did during World War II.

Time and again – in 1919, in 1945 and in 1989 – the power balance principle has been declared coffin-ready. And time and again it has resurged. The problem with balance of power is that it encourages arms races. During the Cold War, the two blocks matched each other, missile by missile ad absurdum. The Americans developed a cannon that could shoot nuclear charges, “M65 – Atomic Annie”. The cannon being unusable did not prevent the Soviet Union from making a copy.

Balance of power is what historian AJP Taylor called a “perpetual quadrille” characterized by vigilant distrust. Therefore, we have seen a number of attempts to replace the balance of power mechanism. After the Napoleonic Wars, the great powers attempted to establish a ‘security council’, the European Concert. The scheme was short-lived. Later, one sought to create a world parliament, first with the League of Nations, later with the UN. Neither did become the agency of shared authority that many had hoped for.

With the end of the Cold War, many hoped that time was ripe for a new way of regulating international politics. In Europe, integration has helped break out of the cycle of increasingly devastating wars. But what A. J. P. Taylor called the dream of a “a painless revolution, in which men would surrender their independence and sovereignty without noticing that they had done so” has not come to pass.

States remain the indispensable players in the international system, now as in the past. States have competing national interests. What French Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine called American “hyperpower” does not serve everybody’s interest equally. So, what can we expect from a world governed by the balance of power? Let me start with the positive. The power balance principle encourages competition. Competition contributed to the innovation-friendly climate that made the West kickstart globalization.

Another possible advantage is that power balance does not require supranational governance. In such a system, the independence of weak states will be preserved by the mutual distrust of the great powers. Apart from arms races the great disadvantage of power balances is that it encourages suspicion and rivalry. The UN Security Council is today deadlocked in a manner not dissimilar to that seen during the Cold War. Over the Syrian conflict Russia and China have shown that the reluctance to see a friendly regime overthrown weighs heavier than the moral imperative to stop using chemical weapons against civilians. This is immoral, but the logic of balance of power politics is not a moral one.

What does the United States want?

China, Iran and Russia represent Donald Trump’s geopolitical triangle. All three are now made to feel that the United States remains the center of the international order it created. They each challenged U.S. authority – and are now suffering the consequences. The U.S. is in a trade war with China. Washington has penalized Chinese exports in order to force a renegotiation of the overall trade relationship. This has set off the alarms in Beijing. The country was not prepared for this, not yet. The export-driven economy is vulnerable.

The Chinese are therefore keen to reach a negotiated solution, but assume (with some justification) that Trump will demand more if they concede without a fight. While the U.S. under Obama tried to understand the Chinese, the anthropological burden is now on China. Beijing has proved surprisingly inept at understanding the West. Attempts at counter-sanctions underlined, if anything, just how little the Chinese buy from the United States.

Beijing has since signaled a willingness to correct the Sino-American trade imbalance. All they ask is that this happens quietly to avoid a loss of face. But Trump wants China to lose face. That is part of the point. As it was when the Chinese in September 2016invited President Obama to Beijing and denied him the red-carpet treatment they offered other leaders. Trump wants the world to see.

What happened? A Washington insider said it with the following words: “The war between the ‘Ikenberrians ‘and’ Mearsheimians ‘is over and the latter won.” He was talking about two foreign policy schools, each named after a scholar-sage, G. John Ikenberry and John J. Mearsheimer. Ikenberry has argued that if China is allowed to grow within the established institutional frameworks it will, eventually, become the custodian of a liberal world order. Therefore, the West would be advised to clear a place in the sun. When he spoke to billionaires in Davos in 2017 China’s leader Xi Jinping did his best to come across as a liberal internationalist.

Mearsheimer – on the other hand – views China as an autarchy that has sapped the West of vitality by making common cause with the Davos elites. Together they transferred the technology and production capacity – the sources to the Western prosperity – to China. He sees in China a strategic rival that must be balanced. This view is today dominant in Washington. China committed two major blunders. They took advantage of Obama’s wavering and fortified contested islets in the South China Sea, contrary to assurances. And they announced ambitions to strip the West of its leadership in High Tech in the “Made in China 2025” strategy. That even woke up the drowsy Europeans.

Many in Europe had forgotten that China is a non-democracy which practices mercantilism in a nominally free trade system. For two decades Chinese money has had free reign in Europe, hovering up the industries and technologies that pays for their expansive welfare states and postmodern politics. Through hidden subsidies, artificially low currency and restrictive home markets, China has been able to enjoy the best of both worlds. The country played small while it grew to be a superpower

Western elites made this development a virtue of necessity, because cheaper consumer goods masked wage stagnation in Europa and America. Many workers made the same as before but could buy more consumer goods for their wages. If the U.S. continues to increase the pressure, China may be forced to open its markets, but it can also lead to price increases and political instability in the West. American foreign policy has undergone a change of hands under Trump. Under Obama’s foreign policy of managed decline’, they sought to breathe new life into the Nixon Alliance between the United States and China. They even spoke in hushed voices of recreating a strategic partnership with Iran.

In that perspective, Russia was an irrelevant irritant; “A medium-sized dog with big dog attitude” to borrow wikileaks’ description of a Swedish Foreign Minister. In Trump’s foreign policy it is not enough for Iran to abstain from nuclear weapons. Teheran must also be denied hegemony in the Middle East. The Trump Administration sees Moscow as a natural partner. Of course, Russia must make amends to get out of the sanctions that are hobbling the economy, but there is really a way out because the Americans are eager to avoid an actual alliance between Beijing and Moscow.

What can be learnt? One lesson is that the U.S. now stands willing to use its central role in the world economy to strategic effect. The U.S. President remains opposed to ‘humanitarian’ wars and lacks patience with abrogating allies. Turkey received the economic version of a slap to the face when it refused to hand over an innocent American jailed in Turkey.The American sanctions shook Turkey’s economy in 2018 and showed other NATO Allies that the Trump Administration views the Alliance more as a community of interests, than as a community of values. The many allies who plan to renege on the promise to spend two percent of GDP on defense by 2024 may have a nasty surprise in store.

The other element is that the U.S. is planning a large navy buildup. Trump has announced plans to build 40 new warships over the next five years, although that number seems unrealistic. The goal is nevertheless a 355-ship navy, capable of absorbing losses in a potential conflict with China. In this, as well as in President Trump’s address to the U.N. General Assembly in September, the intellectual fingerprints of Steve Bannon remain clearly discernable. The former Chief Strategist may have left the White House but his ideas have not.

Looking beyond the much tweeted: “We reject the ideology of globalism and accept the doctrine of patriotism”, the speech was remarkable for its detail and candor, making it arguably the most significant foreign policy address given by a U.S. president for some time. Things have changed in Washington. Among those who determine U.S. Foreign Policy, it is hard to find anyone who has not read Graham Allison’s book “The Thucydides trap” which foreshadows war between the United States and China.

The Thucydides trap

“In short, we do not want to put anyone in our shadow, but we also demand our place in the sun.”. During a foreign policy debate in the German parliament in 1897, Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bülow articulated the foreign policy ambitions of Imperial Germany. Behind the courteous request lay a hidden threat. Power is a scarce commodity; If someone wants more, others will have to get less.

In 1907, Eyre Crowe of the British Foreign Office wrote a famous memorandum explaining the Present State of British Relations with France and Germany.” He concluded that Britain should face the rivals “unvarying courtesy and consideration” while maintaining “the most unbending determination to uphold British rights and interests in every part of the globe.”

Crowe saw Germany’s growing power and prestige as a threat to Britain’s Empire. Clearing a space in the sun for Germany was not an option. Four decades later, George F. Kennan drew similar conclusions in the “Long Telegram”, which outlined what would become America’s ‘containment strategy’ against the Soviet Union. The communists should not be allowed increase their power at the expense of the United States.

In 2019, the relationship between the world’s leading military powers, the United States, Russia and China has deteriorated sharply. In spite of China’s endeavor to portray it’s rise as benign; the United States has grown troubled. China’s economy is about the size of that of the U.S. and the country is increasingly assertive on the international arena.Washington has been losing patience with China’s ‘head-I-win-tails-you-lose’ approach to free trade for some time.

But Donald Trump’s tariff war against China is about more than trade. It is about power, who is to dominate the international system in this century. The Trump administration justifies its current sanctions on the grounds of national security. They accuse China of rigged economics and state-sanctioned theft of U.S. technology. The focus is on the ten sectors highlighted in the mentioned report “Made in China 2025”, Beijing’s strategy for industrial dominance.

At the same time, dealings between Russia and the United States have probed new lows. President Trump claims relations are worse than during the Cold War. We are, fortunately, some way away from the Cuban missile crisis, but since the Crimean annexation, mutual suspicion has been growing, accompanied by mutual sanctions and expelled diplomats.

The war in Syria started as a civil war but has developed into a regional conflict and an arena where the great powers use armed force as a form of communication. Many have meddled. Russia was the most determined and warned the United States against any military intervention in Syria and warned against the “most serious consequences”. Some were worried that Syria could lead to great power war. That was always unlikely. Mostly because no one is prepared for a major war. The danger is that such preparations are now getting under way. The relationship between states can be compared to a bank account where co-operation creates ‘trust capital’ and conflict spend the same. Over the past decade the great powers spent far more than they earned.

Although Russia is in some ways resurgent, the country cannot compare with the United States. China, on the other hand, is a super power on the making. And if Russia and China make common cause, the West has a genuine challenger. But Beijing shows little interest in allying with Moscow. It would likely take something momentous to force such a union. Yet Beijing is worried about whether the U.S. will try to stifle China by denying the country access to the resources it needs to grow. In the United States, a number of commentators have advocated such a containment strategy, while the Bush and Obama administrations welcomed official China’s growth. Trump seems to favor containment.

Peaceful power shifts are the exception in history. During a visit to Washington in September 2013, China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, referred to fifteen historic cases of rising powers. In eleven of these cases, “war has broken out between the new and established powers.” Wang did not list any cases he referred to. Professor Graham Allison rode to the rescue with his book The Thucydides Trap. The term refers to the Greek general Thucydides’ explanation of the Peloponnesian War. It was “The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable.”

Allison investigates 16 historical cases where a major power threatens to surpass another. Three quarters ended in war. He concludes that war between China and the United States is likely, but not inevitable. Much will depend on how the West handles its challengers. To include or to isolate? That is the question.

Robert Jervis’ “Perceptions and Misconceptions in International Politics” (1976) is about situations like this. Here, the political scientist points out that states that perform what is perceived as threatening acts do so for two very different reasons. In some cases, aggressive behavior does not come as a response to a perceived threat, but as a result of aggressive leaders or ideological motives. A classic example is Napoleon Bonaparte. In such cases, attempts to negotiate and compromise will not work. Deterrent behavior is the only effective alternative.

Own military strength, clear “red lines” and a willingness to follow up the threats are the only way out when facing an irrevocable revisionist great power. The hawks in the US believe Xi’s China falls into this category. The other main category is aggressive behavior motivated by fear or uncertainty. In such cases, threats and hardness may help to confirm this fear, creating a corresponding sense that any sign of weakness will be exploited. The danger of this scenario is an increasing spiral characterized by increasing hostility. In situations where aggression is based on real fear and uncertainty, the best solution is accommodation..

In other words, the outcome of the current trade war is likely to have consequences far beyond trade imbalances.

Published in The American Interest 23.07-2019